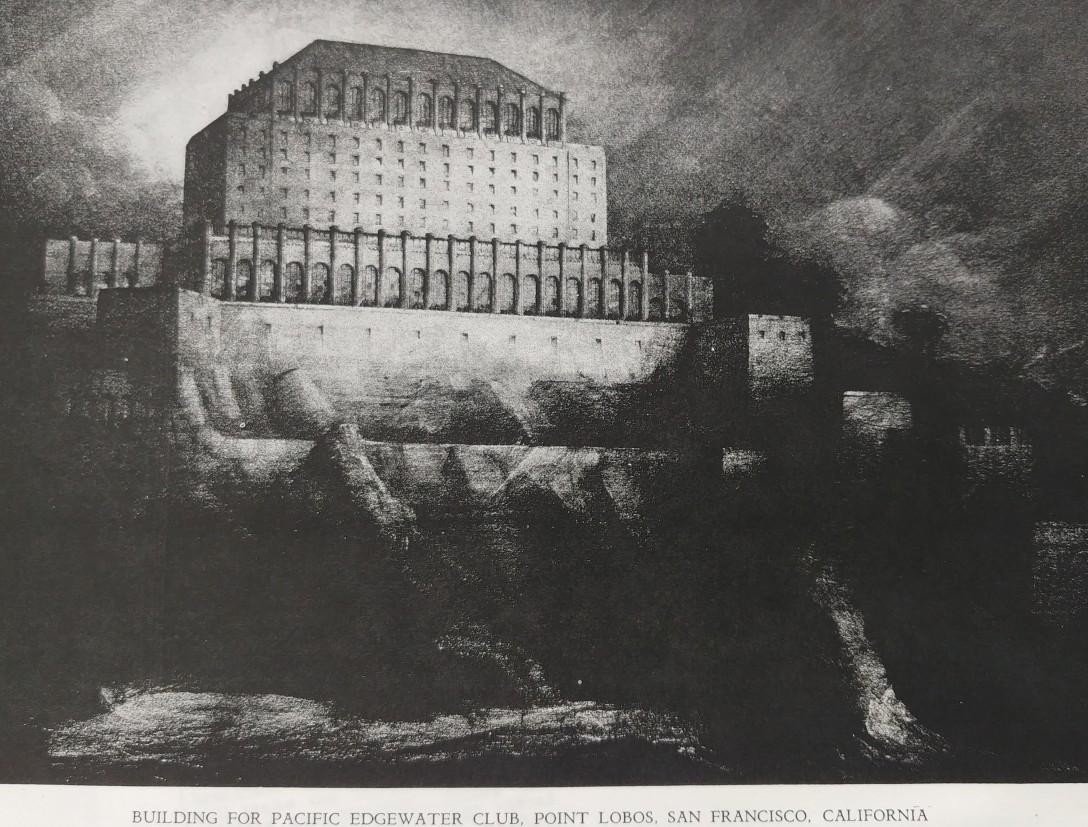

The story of the unbuilt magical social club that exists only on paper is typical of the 1920s: it involved oceanfront real estate, a private club seeking out the well-to-do and nouveau riche, beauty queens, suspect business machinations, a grand jury investigation, and an ultimate lack of funds for the oversized ambitions of everyone involved.

Category: Moderne

The El Rey Theatre to come back as a movie palace for a night

The El Rey Theatre, the former movie palace that still towers over Ocean Avenue and parts of Ingleside Terraces, is turning 80 next month. To celebrate the anniversary, the Voice of Pentecost, which bought the building in 1977, is hosting a fund-raiser, and the organizers will be showing the same film that was featured during… Continue reading The El Rey Theatre to come back as a movie palace for a night

The Transbay Terminal Will be Missed

With the looming demolition of the Transbay Terminal approaching next month, one might expect to see the inevitable stories about the building's better days in the local press. Sadly, the Sunday piece by Carl Nolte in the San Francisco Chronicle does not do the building justice. Too many have judged the 1939 building's architectural merits by… Continue reading The Transbay Terminal Will be Missed