“Last night I dreamt I went to Manderly again….

There was Manderly, our Manderly, secretive and silent as it had always been, the grey stone shining in the moonlight of my dream…” From Rebecca, by Daphne du Maurier

There are always unresolved mysteries to explore while researching history. In the world of architectural history, mysteries can include projects that were never built. In the life of San Francisco architect Timothy Pflueger, one of his more intriguing yet unexecuted projects was a monumental private club and resort called the Pacific Edgewater Club, planned during the roaring 1920s for the bluffs overlooking Point Lobos, part of the vast oceanfront property once owned by Adolph Sutro, and today part of Land’s End.

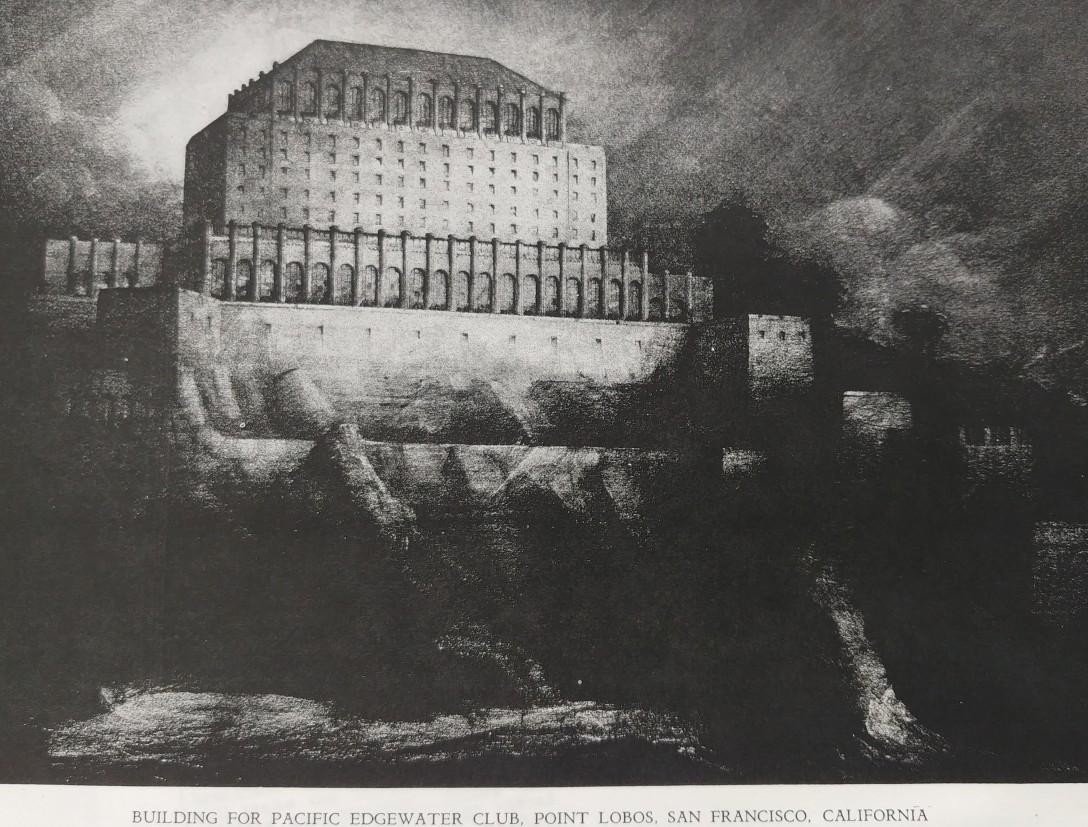

This unrealized project of Pflueger’s has always fascinated me and I had no room to include it in Art Deco San Francisco. Once you have seen the dark and brooding version as rendered by the famous architectural delineator, Hugh Ferriss (above), it’s easy to imagine how magnificent it would have been, perched high among the rocky, seemingly foreboding terrain above Point Lobos.

The story of the magical club that exists only on paper is typical of the 1920s: it involved oceanfront real estate, a private club seeking out the well-to-do and nouveau riche, beauty queens, suspect business machinations, a grand jury investigation, and an ultimate lack of funds for the oversized ambitions of everyone involved.

The “highest knoll” in the Sutro Estate

The story begins in 1926, when a group of men, some based in Los Angeles, formed an exclusive club and purchased a section of the ocean-front property at Point Lobos from Adolf Sutro’s estate. In May, 1926, the San Francisco Examiner reported that a new membership organization, called the Club Farallon was to be built upon a scenic spot overlooking the Cliff House, occupying “the highest knoll in the Sutro estate.” The estimated $1 million club was to be financed through the sale of lifetime memberships. It would have a rooftop dining room for nightly musical reviews, and an observation lounge 300 feet long with unobstructed views of the Pacific Ocean, where one could see the Farallon Islands from the rows of proposed windows.

One month later, the San Francisco Chronicle reported that Miller & Pflueger architects had been selected for the new club and building was set to begin October 1, 1926. At the time, architects James R. Miller and his younger partner Tim Pflueger, were riding high on the success of the new corporate headquarters for the Pacific Telephone & Telegraph Co., which had been completed in 1925. The city’s first true high-rise skyscraper with setbacks also had unusual embellishments in the Moderne style that many decades later would be referred to as Art Deco. An ode to that skyscraper at 140 New Montgomery Street, known locally as the Telephone Building, even appeared on the same page of the Examiner, next to the story announcing the Club Farallon’s formation in May, 1926.

In addition to being popular in the moment, both Miller and Pflueger were club men, as were many architects and business men of the era. They both belonged to The Family, a private club formed by former Bohemian Club members, and the Olympic Club, where Pflueger would take his daily swim. These San Francisco private clubs were at the time (and some still are) for men only, while the city’s prominent women had their own social clubs such as the Metropolitan Club and the Francisca Club. A novel aspect of both the Club Farallon and its successor, the Pacific Edgewater Club, was that they were conceived as private social clubs for men, women and their families.

A drawing in the San Francisco Chronicle in mid July was the first rendering published: a massive building faced in stucco, with two wings, organized around a colonnaded courtyard, designed in the Spanish Colonial revival style. A long walkway framed by low manicured box hedges led to a detailed entrance, with ornamental stucco in relief, possibly in a detailed Churrigueresque style. This rendering was signed by Francis Todhunter, a commercial artist who was then working for the H.K. McCann advertising company, one of the precursors to the McCann Erickson advertising agency. It is likely that this quick sketch did not yet involve the newly hired architects.

There is no indication of the sea or its stunning views in this first drawing, which served as an ad to draw in more members. Membership cost $400 before July 21, when the price jumped to $500. Membership was by invitation only, according to the ad. The public was invited to view the area to be built from an observation tower at the corner of Point Lobos Avenue and what was then called Harding Boulevard (now El Camino del Mar). Today, that area, just north of the old Sutro Baths, is all walking trails, a seemingly naturalistic setting, but one that has been interfered with by man over centuries, as described in this excellent cultural landscape report on Lands End by local historian John Martini.

“Guns and search lights”

Another possible connection to Miller & Pflueger was the law firm working with the club, Heller, Ehrman, White and McAuliffe, a firm they worked with frequently. Pflueger first met with the leader of the club, Justice B. Detwiler on June 1, 1926, where he recorded in his date book that he looked over the sketches they had done. He suggested closing off some streets to nearby Fort Miley. In July, Pflueger recorded that he went to Fort Winfield Scott in the Presidio with J.R. and Detwiler, where they met with a Colonel Halsey to talk about “guns and search lights.” There is no further explanation, but Pflueger probably wanted to find out what was left of the prior fortifications of the site. Two and a half decades after the the site was first surveyed after the U.S. Civil War, the Army secured a large section of Lands End for development as a coastal defense site, according to Martini’s report, calling it the Point Lobos Military Reservation.

Pflueger probably wanted to find out from Colonel Halsey if the batteries constructed during the Spanish American war contained any active artillery that could pose a danger in construction, since his post was also in charge of Fort Miley. The mention of search lights could have been a consideration in the design of the club, especially since the area of Point Lobos was known for ship wrecks and tragically, a location of frequent suicides in the 1920s. Martini discovered that there were so many suicides in the area that the city morgue maintained a journal called “The Death Lure of Land’s End.”

In mid July, the executive committee and the membership committee of Club Farallon hosted a dinner at the St. Francis to celebrate the first 1,000 life memberships in the club.

The state Commissioner of Corporations investigates

Suddenly, nearly three months later, the Farallon project was in tatters. In early October, the Chronicle reported that California’s Commissioner of Corporations had conducted two investigations of the club, and that on the order of the commission, its checking accounts had been put in escrow. The title to the property it had reportedly acquired from the Sutro estate was also said to be “clouded.”

At the same time, another group calling themselves the Pacific Edgewater Club emerged with a deal to purchase a separate plot of land facing the Great Highway, near Vincente and 47th Avenue for $220,000, and sought out the Farallon members to join. The lot was adjacent to the popular Tait’s-on-the-Beach, a roadhouse restaurant with good food, music and dancing. It was so popular in the 1920s that it makes an appearance as one of the hot night spots for the Jazz Age smart set in the 1925 novel “Chickie,” which was set in San Francisco, by Examiner writer Elenore Meherin.

The Pacific Edgewater group proposed merging their fledgling club with members of Club Farallon into their enterprise, by transferring the Farallon memberships to the new club. The property along the Great Highway was sold to the Pacific Coast Holding Co., headed up by two Los Angelenos, Frank A. Simmons and Fred F. Jamison.

A brief flurry of stories appeared about the rift between the two groups, and a row that took place at the Down Town Association. Eventually, 80% of the Club Farallon members agreed to join the Pacific Edgewater Club, believing their membership fees would then fund the next oversized plans for this club’s quarters, now along the Great Highway. In early December, the new club announced they had hired Miller & Pflueger as the architects for a U-shaped building fronting the ocean esplanade of the Great Highway. The eight story building would have 250 rooms, a roof garden, ballroom, gymnasium, two swimming pools, card rooms, a library, locker rooms and showers for men and women and a children’s playground. A putting green, tennis courts and handball courts were also envisioned.

But in Pflueger’s datebooks, he appeared to be increasingly skeptical of the whole project. He had many projects going on in 1926, including other entertainment palaces in the forms of movie theaters — the Tulare in the Central Valley and the Royal on Polk Street in the city. In late November, after a meeting with J.R. Miller and the Edgewater’s Jamison, the firm agreed to take the project on, on a regular business basis. “That is if [the] thing flops, we are to be paid for work done,” Pflueger wrote. By mid-December, a few former members of the Farallon Club had filed law suits to get their money back, according to filings cited in the Recorder, a San Francisco legal newspaper.

On Christmas Day, 1926, the Chronicle published the first rendering of the club by Miller & Pflueger, and an estimated cost of $2 million. It is possible that the architect did not want to spend too much time on the risky project at that point. Two dramatic centerpiece staircases in his drawing lead down to the highway itself. Patrons would have to cross the highway to get to the beach, if they were inclined to leave the luxurious surroundings.

The Chronicle quoted Pflueger saying building would begin “as soon as possible” after the completion of interior plans. The style was described as both Spanish, with “exotic ornament of Oriental design, symbolizing San Francisco as the entrance to the Orient,” a theme he embraced for the lobby of the Telephone Building and the ceiling of the Castro Theatre.

Pflueger or one of his draftsmen in the office also did a set of interior sketches and drawings, which were photographed and are now in the archives of the California Historical Society. The dramatic pool that was shown in the Chronicle was surrounded by expansive floor to ceiling arched windows, with an unusual ceiling motif above the pool.

Surprise news of a new venue

At another big luncheon at the St. Francis Hotel at the end of February, 1927, Simmons, the president of the Pacific Edgewater Club, announced that the group had purchased six acres from Dr. Emma Merritt, the daughter of Adolf Sutro. Both the Chronicle and the Examiner ignored the fact that this was the same land that had been purchased just a year previously for the Farallon Club, a deal described as having a “cloudy title.” Dudley Westler, the Chronicle Real Estate editor, gushed about the latest plans for a “magnificent club building,” and swallowed the following anecdote, hook, line and sinker.

“The decision to change the site for the proposed club was reach by Simmons almost by accident,” Westler wrote. “He had formerly purchased a site near Tait’s-at-the-Beach, but when it became apparent that a larger site was necessary to really do the club justice, he happened to get off the main boulevard long enough to grasp the magnificence of the view at Point Lobos.” The six acres, he noted, was virtually “all the rugged ocean view water front property available in San Francisco,” outside of the homes long sold out at Sea Cliff.

Buried further in his story, Westler wrote that an $850,000 bond issue “has already been offered by a substantial financial house.” It does not appear, though, that the bond issue, which would have put the group even further in debt, was ever ultimately offered. The story was accompanied by a photo from the luncheon with Pflueger and Frank Carroll of the Down Town Association, standing in front of a massive rendering of the club and the site. Pflueger looks a tad out of character, with a slight morose look as he tries to smile.

One month later, Pflueger appeared to be taking the project more seriously. Hugh Ferriss was in the office in March, and Pflueger hired the New York-based architectural delineator for a rendering. The result was the dark, moody image of the proposed club, evocative of Point Lobos on a stormy night, in his signature style. Ferriss had drawn the Telephone Building for Pflueger after its completion, a stunning work that is today in the collection of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. The design was very similar to the club on the Great Highway, minus the oddly positioned staircase, with an enormous foundation that gives the proposed building with rows and rows of arches an almost institutional feeling.

Pflueger also had a meeting with Simmons and the builders Lindgren & Swinerton to discuss the foundation. At one meeting at the site, Pflueger noted they were joined by Sutro’s then 70-year-old daughter, Dr. Emma Merritt, who walked with them, “despite the dampness.” The Chronicle reported that a “stout fence” had been built around the property and pathways and stairways for pedestrian descent. An office was to be built on Merrie Way, at the ruins of an old signal house, once the home of a watchman who sent flag signals to Telegraph Hill on the approach of incoming ships.

A “Breakfast Club” amid the cypress trees

Nothing more appears in Pflueger’s datebooks for a few months, but the club organizers continued to promote the club, seeking to raise the membership. At some point the organizers printed a four-page brochure on thick paper stock that opened up to the big rendering of the club and its site, done by Pflueger and his draftsmen. Color cartoons also portray elegant couples dining, dancing and ready for outdoor activities. The brochure also noted that some members, “the married and unmarried alike, propose to make the club their permanent home, while many others will take apartments for the week-end.”

A June article on the progress of the club said that the club had a “large membership,” but that it needed two-thirds of the roster to be completed before construction could begin. No further details were provided.

Another promotion was unveiled, where the club organizers hoped they could seduce potential members if they came to the magical venue for a bracing breakfast.

In mid-July, a chilly and foggy time of year in San Francisco, especially in the western part of the city, the club hosted a “Breakfast Club.” Over 250 guests were invited to partake in a regal morning feast, amid “a magnificent growth of age-old cypress trees” that formed a “natural amphitheater and affords shelter from fog and winds.” The group constructed a large horseshoe table and an enormous outdoor grill, covering a brick oven, where they served fruit, hot cereal, muffins, crisping “ham and” and coffee. Sounding like real estate hucksters selling time-shares, they laid on the hyperbole. “The aroma of full rich coffee will drift about in the air mingling with the pungent suggestion of burning woodland fires and the tang of the restless sea,” club president Simmons was quoted in the Chronicle.

A few weeks later, the Breakfast Club hosted a group of beauty queens, in San Francisco for “California Beauty Week,” the week leading up to the Miss California amateur beauty pageant. On a Sunday morning, Grayline buses and Hertz “Driv-Ur-Self” sedans picked up the 60 lovely young contestants at the Mark Hopkins for the drive trip out to Point Lobos. Bedecked in cloches, silk stockings and fur-trimmed coats befitting the chilly July air, the beauties dined at the giant horseshoe table on their “ham and,” chatting with club members, accompanied by peppy music. Breakfast was followed by brief entertainment: vocal solos, a monologue by KPO radio host and vaudevillian Dan Casey, and some burlesque stunts. Then they were treated to an air show by a trio of Pacific Air Transport planes, their “air escorts.”

For the rest of 1927, all was quiet. In January, 1928 Pflueger had a meeting with some executives on the topic of the club, and the next day, Frank Simmons came to his office. Pflueger wrote that he told Simmons the results of the meeting, but he left no further explanation. No notes of any further progress in the building itself were in his datebooks. In mid-March, Simmons, Al Swinerton of the building firm, and two others met in Pflueger’s office, and discussed a “public club” proposition. The club executives must have been contemplating opening the club up to the general public, to increase membership rolls to meet their grandiose plans.

A former beauty queen’s ire, the bunco squad and a grand jury investigation

In June, according to the Recorder, a lawsuit was filed against the Pacific Edgewater Club by a vendor, the Trans Credit Traders, for $950. And at the end of August, the wheels came off. Members Iantha Henderson and Marie Pappas went to the police and filed a complaint against the club, seeking a return of their $400 in individual membership fees, which according to an inflation calculator would be worth around $6,000 today.

The ladies complained about high-powered salesmanship, and a club membership that started out resembling the social Blue Book of San Francisco, with bankers, doctors, brokers and other social leaders, only to see the list becoming less select. After paying $200 in 1926 to join the Club Farallon, when that club went defunct and its members were offered memberships with the Pacific Edgewater Club, the two went to Simmons’s office on Montgomery Street to talk to him.

“He is the man that has seven telephones on his desk,” Henderson told the Examiner. “He is always so rushed, talking on all the lines at once. He coaxed, begged to me pay the balance, which I finally agreed to do.” Henderson was also a former beauty queen, when in 1915, she was chosen to portray Eureka at the Portola Festival, an irony considering the club’s use of beauty queens as part of its promotion. She wrote Simmons a letter in July, asking for her money back. “I paid $400,” she wrote. “So far, there is no club, and no visible prospects of one, after waiting about two years.” When she visited the club offices again, Simmons was not in and she was told to write to a club official in Los Angeles. That letter was returned, and then she decided to go to the police.

The San Francisco Police Department and the District Attorney’s office agreed the events seemed suspicious, and the city’s bunco squad was assigned to look into the potential fraud. “Promises were made in 1926 that the club would be built within a year,” Deputy District Attorney Milton Choynski told the Examiner. “So far, not a shovelful of earth has been turned on the site.” When reporters went to the club offices, they were told the Pacific Edgewater Club had moved two months previously and had left no forwarding address.

The Chronicle reported then that the organization had deeded the six acres of land back to the Sutro Estate, and the detectives who investigated the matter concluded that “the promoters started something they could not finish.” The State Corporation Commission said hundreds of complaints had come into its office, but it had no jurisdiction to investigate. When the Club Farallon was initially formed in 1926, the Corporation Commission was about to charge the individuals with selling stock without a permit, but the Attorney General ruled it had no jurisdiction over the club’s plan to sell memberships. The Assistant DA said he didn’t have enough evidence to bring the Club Edgewater case to the grand jury.

One month later, in early September, the disgruntled club members again met with the city’s chief of detectives and made a formal demand to Simmons to produce the club’s complete records, which they said had not been made available to them. A few days later, Assistant DA Choynski said that he was presenting the case to the grand jury.

In the middle of November, the grand jury concluded there was no evidence of fraud in the management of the club, and its cessation of building operations was due primarily to the failure of its membership drive. The club had spent too much money for advertising and acquiring the Point Lobos property. In an odd coincidence, florist Angelo Rossi, who later would become the mayor of San Francisco, as well as a client and friend of Pflueger, was the foreman. “It appears that the club undertook too many expenditures at one time and ran out of cash. But there was no evidence of fraud,” Rossi said, according to the Chronicle.

Since the Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley, the home of the Pflueger archives, is currently closed because of the pandemic, it’s not possible right now to find out if anything more substantial will turn up in the office correspondence, or Pflueger’s further thoughts on the pipedream. But it seems clear even from his quick notes that no matter how interested he was in the project, he was leery about the grand plans from the get-go, and was always conscientious that the firm be paid for the work that it did.

Perhaps, in the end, San Francisco and its visitors are better off without the imposing edifice, which might have blocked access to the trails, nature and gorgeous views at LandsEnd, had this exclusive club actually been built. Even so, the lure of this stunning, magical site can lead one, like the narrator of the popular late 1930s novel, Rebecca, to dream of a magnificent property by the sea. Instead of being damaged by fire like the fictional Manderly, the dream of the Pacific Edgewater Club was ruined by hucksters and hubris, for it may have been just too grand, even for the roaring 1920s.

Fascinating! I can see why Pflueger might have been uncomfortable with this enormous project!

Thanks for telling this story, Therese! I vaguely recall hearing something about it before–maybe you told me of it, or mentioned it in one of your presentations. I’ve been in love with the area from just north of Lands End down to Sutro Heights since I was eight. It’s so haunting. I wonder what the vibe would have been had the club building been built. By now, it would probably be adding to the bewitching, wind and fog-swept vibe.