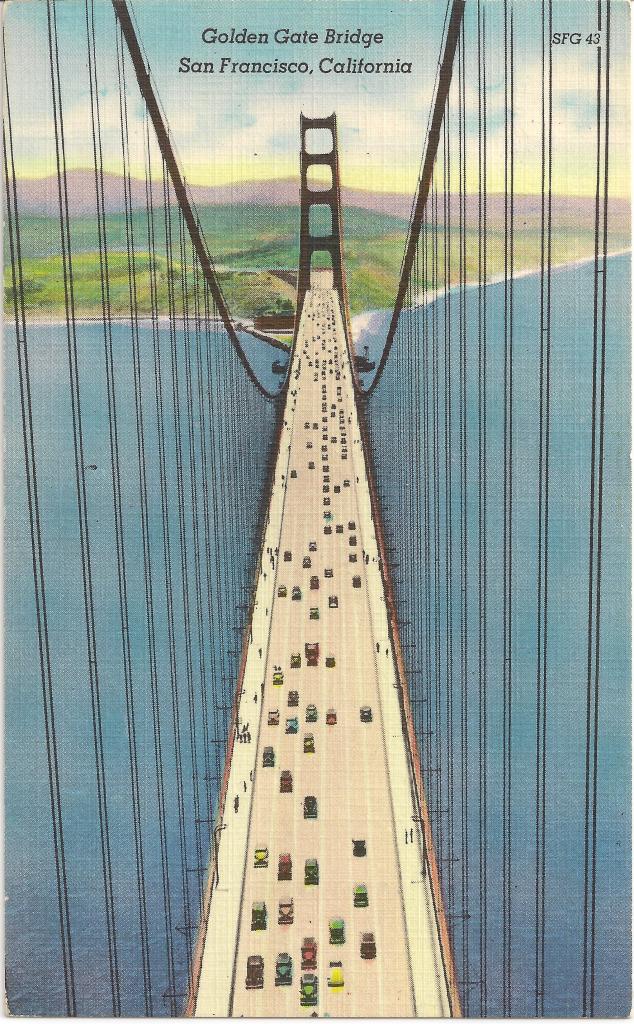

San Francisco’s iconic Golden Gate Bridge will celebrate its 75th year in service next month. Big festivities are planned all over the city, including a “spectacular event” organized by the bridge authority for May 27 at Crissy Field. A special website has all the details for the upcoming Golden Gate Festival. This year, there will be no bridge walk and the landmark will remain open to auto traffic, as officials seek to avoid a replay of the last big anniversary party.

Locals will undoubtedly remember when the bridge turned 50 in 1987, 800,000 people turned out, when only 50,000 had been expected. The bridge became so overloaded with an estimated 300,000 celebrants that it flattened out in the center. Officials told reporters at the time that ”the bridge had the greatest load factor in its 50-year life” and a paper later written on the event said the suspension cables were “stretched as tight as harp strings.”

Fabulous exhibit at California Historial Society

Before the festivities in late May, there are plenty of ways to start celebrating now, including seeing some local exhibits around town on building the great bridge. One exhibit that will be of interest to architecture fans is a fabulous show on the history and the evolution of the bridge at the California Historical Society. The exhibition, the first under new executive director, Anthea Hartig, is called “A Wild Flight of the Imagination.” The title was borrowed from a promotional pamphlet written in 1922 by chief engineer of the bridge, Joseph Strauss, and city top engineer, Michael O’Shaughnessy. In that brochure, the two, who would later spar when O’Shaughnessy opposed the bridge, wrote that the bridge, once “considered a wild flight of the imagination, has…become a practical proposition.”

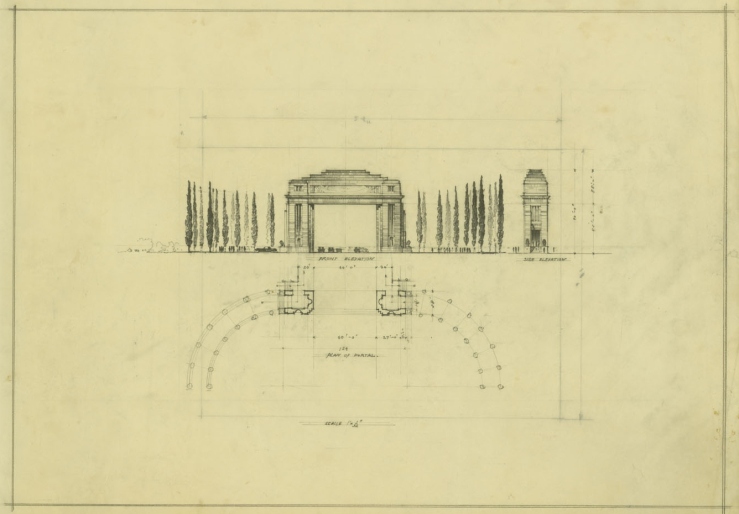

The CHS exhibition, which runs until October 14 , is a must-see for anyone interested in the bridge’s fascinating history. Especially intriguing are the fantastic renderings of concepts that were never realized, such as a dramatic Beaux Arts/City Beautiful promenade that would have lead to the bridge, and its not-so-well-known influences.

Influence of the theatre architect John Eberson

One of the most interesting elements of the exhibit is the obvious influence that theatre architect John Eberson had on the bridge from his brief work as a consultant to Strauss. Eberson is not exactly a household name but he is well-known to theatre historians as the father of the so-called “atmospheric theatre” and the designer of over 500 theatres around the U.S.

One of his more famous theatres in the U.S. is the Loew’s Paradise in the Bronx, New York, which opened in 1929 on the then-thriving Grand Concourse, which was recently restored in 2006. The Paradise was one of his three atmospherics in New York City, in which the architect sought to bring the outside indoors, typically with mechanics and lighting. These theatres often gave audiences the impression of seeing movies under an evening sky, with the moon and clouds moving overhead. Eberson, a native of Austria, worked in St. Louis, Chicago and other cities before moving his office to New York in 1926, according to his obituary in March, 1954 in the New York Times.

Strauss hired Eberson to work on the towers and some of the approaches on the San Francisco side of the bridge. As Kevin Starr described in his 2010 book, Golden Gate:The Life and Times of America’s Greatest Bridge, “the very fact that Strauss initially chose Eberson to stylize the towers and other aspects of the bridge underscores Strauss’s sense of the Golden Gate Bridge as, in part, a theatrical production orchestrating site, structure and atmospheric into a unified aesthetic statement.”

If all of Eberson’s drawings, or those of his successor, had been realized, there might be a far more dramatic entrance to the bridge, with a grand colonnade or walled portals, which as John King opined in the Chronicle last month, would have been unnecessary “theatrical trappings,” distractions from the site’s natural beauty. Even so, the dramatic influence of the father of the atmospheric theatre remains today in the bridge’s suspension towers, where the Moderne setbacks in Eberson’s 1930 rendering made it to the completed bridge. According to Starr, Eberson asked for more money to complete the project, but Strauss decided, based partly on a recommendation of local artist Maynard Dixon, and the need to comply with planning changes, to work with Bay Area architect Irving Morrow.

It appears that by August, Morrow & Morrow were fully ensconced in the project, which was still trying to win public approval. An August 1930 article in the San Francisco Chronicle on plans for the bridge getting approved by the bridge district was accompanied by a large photograph of a painting by Dixon that was used to show what the 4,200 foot span would look like in its surroundings. Maynard’s painting was aimed at disproving the increasing opposition that the bridge would mar the natural beauty of the Golden Gate. Irving Morrow noted the controversy at the time. One of his notes, on display in the CHS exhibit, reads: “Sentimentalists tell you it would be a desecration of natural beauty to bridge the Golden Gate,” Morrow wrote. “The point is not whether bridging the Golden Gate will destroy its beauty but whether the particular bridge proposed will destroy it.”

By October, 1930, a series of drawings in the Chronicle’s Sunday photogravure section on October 5 included proposed renderings of the “world’s greatest span,” by Morrow & Morrow Architects. Some echo drawings by Eberson, with a dramatic, neo-classical approach to the bridge on both the San Francisco and the Marin County side. In the drawing of the Marin approach, below, architect Irving Morrow was influenced by both Eberson’s ideas, and Bernini’s colonnade at St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, according to architect Donald MacDonald in his 2008 book, “The Golden Gate Bridge: History and Design of an Icon.” Morrow’s design for the San Francisco portal also called for high walls around a large plaza, acting as a wind barrier, and a grand plan for an exhibition hall.

The exhibit at CHS has several drawings by Eberson, including another approach reminiscent of the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin. But a realignment of the roadway forced a redesign of the San Francisco plaza and money was also an issue. Still it is Eberson’s designs for the 746 feet high suspension towers, that set the tone for the bridge. “Eberson’s design of the towers was very influential I believe,” said Jessica Hough, lead curator of the exhibit. “His tower design was changed very little after Morrow took over as consulting architect.”

The father of the atmospheric theatre may have not worked on any theatres in the Bay Area, but his influence here is profound. MacDonald, who was the first architect to work on the Golden Gate Bridge after Eberson and Morrow, also notes in his excellent book that Eberson initiated the Art Deco style in the bridge. The style in the corners of the suspension tower’s bracing also echoes a theatre proscenium, MacDonald notes, as can be seen in this 1930s construction photo from the San Francisco History Center.

The gradual narrowing of the suspension towers as they rise was an improvement to Eberson’s towers by Morrow, according to MacDonald. Eberson’s stepped pattern in the towers also mirrored the gradual stepping of many skyscrapers built in the 1920s, which echo the pyramid shapes of the temples of the Maya and also allowed more light onto city sidewalks. Timothy Pflueger’s Telephone Building at 140 New Montgomery was the first skyscraper in San Francisco to deploy that technique. Chicago architect Louis Sullivan had suggested setbacks as early as 1891, MacDonald points out. But it was Eliel Saarinen’s second place design of a skyscraper with setbacks for the 1922 Chicago Tribune Tower contest that really brought attention to the concept. While Saarinen’s design was not executed, it was the winner in the architecture community, including unflinching praise from the ever-critical Sullivan, and was far more influential than the actual winner.

With the influence of both movie palace design and skyscrapers of the Jazz Age, no wonder the Golden Gate Bridge wins all the beauty contests, in contrast to her sister bridge, the Bay Bridge, whose 75th anniversary has not received nearly as much hoopla or attention.

Many other local exhibitions on the Golden Gate Bridge

In addition to the CHS exhibit, the San Francisco History Center on the sixth floor of the main library has a new exhibit called “Bridging Minds: San Francisco Reads, 1933-1937,” featuring books, photographs and ephemera of the period and the works of California authors. San Francisco librarian and author Jim Van Buskirk will be giving talks about movies that have featured the Golden Gate Bridge, which has starred in more movies than any other American architectural icon. Not to be outdone, the Marin History Museum in San Rafael has an exhibition on how the bridge changed life in Marin County featuring construction photos from the renowned Moulin Studios, and photos from local photographer Jeffrey Floyd.

Isn’t it proper to give credit where it is due ? The principle publication “The Golden Gate Bridge report of the chief engineer 50th anniversary edition purchased at the bridge retail store has

not given credit to the architects that created the Art Deco design that is so admired. The Engineering principles are truly great but they neglect who did the conceptual design. A rendering in that book by “Michele” shows 5 lanes of traffic on the upper deck and 4 more on a lower deck. Is there any thought of building the lower deck ?

I went back to my source, an article in the Fourth Quarter, 1999 Issue of MARQUEE magazine, titled “America’s First Art Deco Theatre,” by Steve Levin. It is about the San Mateo Theatre. Unfortunately, all he says about the Bridge is, “Morrow was the consulting architect for the Golden Gate Bridge, and is generally acknowledged (along with his wife Gertrude C. Morrow, also an architect) as being the party most responsible for the extraordinary beauty of this great structure. The Morrows are unequivocally given credit for having selected ‘international orange’ for its color.” It would seem Steve Levin was unaware of Eberson’s contribution. Steve was an Eberson fan, of this I know, and had he known about that architect’s involvement, would have mentioned it at some point–certainly in the above-quoted text, aimed at theatre historians.

I did find an online listing of female American architects that gives Gertrude Morrow’s lifespan as “c. 1892-1987.” Not a bad run!

In Steve’s article on the San Mateo Theatre, he quotes an article by William Morrow in THE ARCHITECT AND ENGINEER (December, 1925) in which a Mr. S. Pelenc is credited with designing the wall hangings and proscenium mural for the San Mateo’s auditorium, all of which, according to photos taken at the time, are what we would today call Art Deco. However, despite much Spanish Baroque ornamentation throughout the interior and exterior of the theatre, it is clear in Morrow’s article that he was wanting to go Modern with the building as well, as he was not a fan of historicist pastiche, for the most part–especially furred plaster with no function. The auditorium ceiling was made almost solely of bare wooden planks laid between the chevron-arranged exposed ceiling beams and trusses, a truly innovative approach for the day. The large pendant lighting fixtures, which look to have been paneled in mica, are of a severe geometric design. Much of the wall surface in the auditorium was simply the bare structural concrete, with decorative paint applied in some spots, and plain color elsewhere.

Steve also includes a photo of one corner of the Portal/West Portal (now CineArts Empire), showing the Right organ grille, adorned with Spanish style shields. Aside from these elements, and a scrolled pediment over the exit door under the organ chamber, the rest of the surfaces are adorned only in paint, and that sparingly. The walls appear to be plain cast concrete, with the imprints of the forms visible, and the ceiling is smooth plaster. There is some minimal Spanish styled stencil work along the tops of the walls, but that’s it. Decades later, Steve’s father, Ben Levin, hired Heinsbergen to come and do a decorative remodeling of the theatre, by then renamed Empire. The organ grilles were covered over in smooth plaster, pierced only by ventilation grilles–ductwork having replaced the organ pipes. The vents were surrounded by little painted Greek temple designs. Years ago, when looking at the photo, I quipped to Steve that you could call these Temples of the Winds. This term ended up in a later article Steve wrote about his family’s theatre chain. The Heinsbergen murals continued up the sidewalls, with more Grecian landscape scenery, with cypress trees and other foliage and more Greek architectural motifs. Presumably, these murals still exist behind the current fabric wall coverings. Steve said when his family remodeled the theatre prior to selling it in 1970, that is what was done. The triplexing was carried out by subsequent owners.

[…] https://blog.timothypflueger.com/2012/04/26/golden-gate-bridge-exhibit-shows-surprising-influences/ […]

i originally thought NOT to view the (so-many) exhibits that will be popping up like spring flowers everywhere, but after your well-written and researched article, i feel compelled to see and enjoy it all! thanks so much for the inspiration!!!

Thanks for the nice comments, yes def recommend the CHS show! Are you back in SF?

Wonderful coverage! It’s great to see Eberson’s contributions to the Bridge recognized so fully in print. It may be also mentioned that Irving Morrow (with William Garren) designed two theatres: the San Mateo, in downtown San Mateo, arguably the first movie palace in the US to embody any elements of Art Deco, and the Portal, in San Francisco. The San Mateo still stands as an office and retail building with most elements of its Mediterranean eclectic facade intact, and the Portal (later called West Portal, then Empire, and now CineArts Empire) still functions as a triplex movie theatre, albeit with a completely remodeled interior. Most of its exterior design is intact. Also, the role of Irving Morrow’s wife, Gertrude, in the Golden Gate Bridge design should not be overlooked.

Hi Gary. If you know much about Gertrude Morrow’s contribution to the bridge, feel free to expound when you have time. That would be awesome. I believe there was a mention in the CHS exhibit that says her contribution to the bridge was unclear (I would have to double check but that is what I thought I read?).

Also very cool to know that Irving Morrow designed the theatre that is now called the CineArts in West Portal.